This is an interesting idea I came across recently. Sorites Paradox, also known as the Heap Paradox, describes the following. If you have one grain of sand, you do not have a heap of sand. If you have two grains of sand, you do not have a heap, since it is made of two parts of one grain of sand, which do not make heaps of sand. If two grains of sand do not make a heap, then three grains of sand will not. (…) If a million grains of sand do not make a heap, then a million and one grains will not make a heap. Following this logic, no amount of sand makes a heap. Alternatively, you can start from the top down. If a million grains of sand make a heap, then removing one from that heap still results in a heap. (…) If two grains of sand make a heap, then removing one from that heap still results in a heap, meaning one grain of sand makes a heap.

Confusing, eh? My initial reaction was that this paradox may be inherently flawed; after all, we’re trying to discretize a concept that doesn’t have apparent units. However, that’s precisely the point. Because language generally is more qualitative than quantitative (as opposed to a physics text), we’re going to run into these fuzzy boundaries, unless our language models themselves change. Since I think qualitative language is important, I don’t think that will happen.

A couple examples have shown the importance of this paradox to me, and I think are fun to share. The first may hit close to home for many. I’ve so often told myself, this one potato chip will not affect my weight. If one potato chip doesn’t affect my weight, then two potato chips won’t either. And if two potato chips don’t affect my weight, then three won’t either. (…) 5 minutes later, and I’m halfway done with the family-sized bag of Fritos, which will definitely affect my weight.

How about one that has legal implications. We have laws based on age, and although we can discretize age, there’s lack of clarity when it comes to questions like “Am I old enough to drink?”. Different countries have different drinking ages, and even ages of majority (adulthood) (also what the heck kids are minors in Mississippi until 21). But again, what does it mean to be old enough to drink? Or old enough to consent? It’s easy to recognize Sorites Paradox here, but it’s harder to break out of it, and decide what threshold of sand grains makes a heap. The prefrontal cortex, integral to decision making, finishes forming around age 25; should our laws reflect this?

While I can’t say what thresholds should be made for legal issues, as there should be social and neurological data driving some of those, I do want to comment on the other example I gave. Sometimes formulating the situation in this way may not lead to the best solution. If you’re constantly asking yourself if the next chip will make you fat, chances are you will eat that next chip. Maybe we should fight a vague metric with a more vague approach. Instead of “will eating this next chip make me fat?, what if we asked “is eating chips good for my health?” The solely correct answer here is no. This is relevant to developing and breaking habits; go read Atomic Habits.

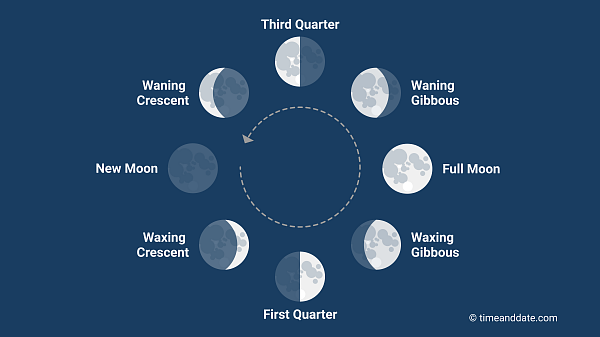

Of course, that approach isn’t applicable in many cases. In a recent group project, we had to teach a computer to learn and predict the phases of the moon. Here’s a tricky question: what amount of light will make a waxing crescent into a first quarter moon?  The approach above would be akin to asking myself whether or not I should be distinguishing different phases of the moon even helps me at all. The anser to that is that we have those phases to describe the moon qualitatively, for fun or for keeping track of the lunar cycle as a measure of time. And having answered that, we have gotten no further in answering our first question.

The approach above would be akin to asking myself whether or not I should be distinguishing different phases of the moon even helps me at all. The anser to that is that we have those phases to describe the moon qualitatively, for fun or for keeping track of the lunar cycle as a measure of time. And having answered that, we have gotten no further in answering our first question.

Quantifying vague concepts is hard! But sometimes it’s really relevant to our lives. Hope this was fun and a cool way to think about some aspects of our lives differently.

Until next time.

See you by the Fire.

M